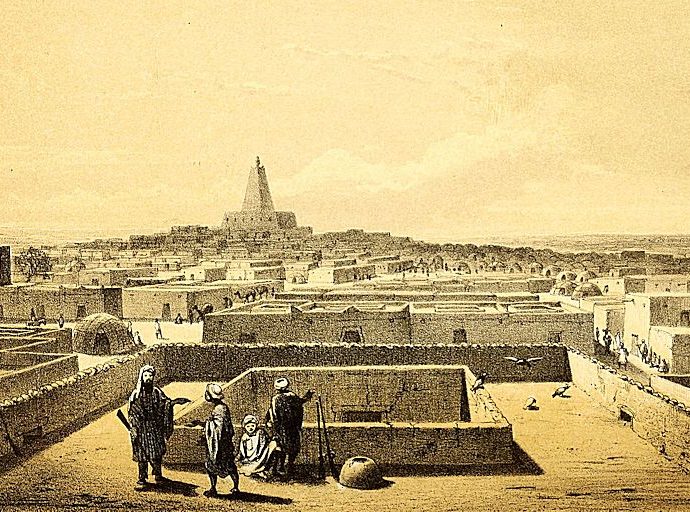

Once, Sorotomo was a vast metropolis, a political centre of the Mali empire. Later, the city was abandoned in the wake of a violent attack.

THE LONG-LOST metropolis at the heart of west Africa’s biggest-ever empire has been discovered by a British archaeologist. Investigations 200 miles south of the Sahara have revealed the existence of a vast city, which appears to have had a population of approximately 50,000 people and to have covered an area of 90 hectares.

Researchers, led by Professor Kevin MacDonald of University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, believe that the archaeological site known as Sorotomo was probably the major political centre and de facto capital of the Mali Empire at some stage in the 13th and 14th centuries – during the height of its power.

“The discovery of Sorotomo is significant because it at last reveals, in tangible form, the sheer scale and sophistication of the medieval empire of Mali,” said Professor MacDonald. “The Mali empire wasn’t just important from an African historical perspective. It was the principal supplier of gold to the Mediterranean/Europe – and thus played a key role in underpinning the medieval world’s economic system.”

It’s estimated that between the 13th and 16th centuries, the empire supplied the Christian and Islamic powers with more than 1,000 tonnes of solid gold. The lost city is being compared to Pompeii in some respects because everything has been preserved exactly as it was in its final hours. A layer of burnt material and scattered human bone has been found – evidence suggesting that it was attacked by the Mali empire’s nemesis, the emerging Songhai empire.

The population either fled, was massacred or was enslaved. Much of what people owned was simply abandoned. So far, only a fraction of the city has been excavated, but already the archaeologists have been able to piece together a snapshot of what life there was like. Finds so far include dozens of medieval cooking and storage pots, grinding stones, spindlewhorls for making textiles, jewellery and cowrie shells (used as money in the Mali empire).

Plant remains indicate that cotton was widely grown nearby and processed in the city, while animal bones reveal the presence of horses, as well as cattle, sheep and goats. It appears the metropolis consisted of a central core (72 hectares) plus a number of satellite suburbs and other building complexes, which covered a further 18 hectares.

The Mali empire was the second and largest of a series of three great medieval empires that rose and fell in the west African grasslands, between the southern fringes of the Sahara and the coastal forests. It was the major political force in west Africa for more than 200 years (1235–1460) and continued in a much reduced state until the early 18th century.

At its peak, the empire consisted of 450,000 square miles of territory – almost nine times the size of England – and stretched 1,000 miles from east to west. It was sophisticated yet adaptive and decentralised, usually retaining at least some of the administrative structures of conquered peoples. Some 14 provinces were divided up into scores of counties and hundreds of local districts.

The population at this time was of many millions. The empire maintained a professional standing army of 100,000 men, including 10,000 cavalrymen. Armed with bows, poisoned javelins and stabbing spears – and swords and lances for the cavalry – the military ensured the empire’s expansion and survival.

Its economy thrived on exporting three major commodities to the Mediterranean and European world: gold, salt and slaves. The emperors, or mansas, introduced radical economic and social reforms, including price control for staples, ‘harmony-inducing’ regulation of relationships between social groups and basic legal rights for slaves.

In a sense, the discovery of the lost city is the culmination of a 120-year long quest. That’s because the search for the site of Mali’s early capital began in the 19th century with an expedition led by a French military officer, Captain Louis Binger. The more recent archaeological and historical investigations, including excavations and oral history research, are expected to continue for several years.