Ovid’s Metamorphoses (AD 3-8) was not originally as controversial as his other poetic works. But as centuries have passed, its notoriety has increased. Recent calls to provide trigger-warnings to university students before they study the work tell us as much about modern Western attitudes towards sex, violence and censorship as the Metamorphoses tells us about the gender politics of ancient Rome.

Ovid’s 15-book epic, written in exquisite Latin hexameter, is a rollercoaster of a read. Beginning with the creation of the world, and ending with Rome in his own lifetime, the Metamorphoses drags the reader through time and space, from beginnings to endings, from life to death, from moments of delicious joy to episodes of depravity and abjection. Such is life, Ovid would say.

The madness and chaos of some 250 stories, spanning around 700 lines of poetry per book, are woven together by the theme of metamorphosis or transformation. The artistic dexterity involved in pulling off this literary feat is testimony to Ovid’s skill and ambition as a poet. This accomplishment also goes a long way in explaining the rightful place the Metamorphoses holds within the canon of classical literature, placed as it is beside other great epics of Mediterranean antiquity such as the Iliad, Odyssey and Aeneid.

But for some, the Metamorphoses sits uneasily alongside its more morally and patriotically sound predecessors. Like a troublesome younger brother, an embarrassment to the family, Ovid’s epic “kicks against the pricks,” to paraphrase the paraphrase of Nick Cave.

The Homeric Iliad (c. 850 BC) soars to the literary heights of the sublime, and shows us how to live and die, to meditate on mortality, to embrace sorrow, to grip and then release hate, to truly love.

The Odyssey (c. 800 BC) takes us on an epic voyage forever leading towards home, sometimes making us laugh, and occasionally letting down its high-brow hair with some sex and infidelity. Yet, appropriate to the gravitas of epic poetry, the Odyssey is also about the journey of a man determined to maintain his heroic stature as he navigates all sorts of dangers in strange lands.

Some 700 years later, when the Homeric verses were still regarded as the benchmark for epic poetry, Virgil composed the Aeneid (19 BC). This Latin epic casts a patriotic spell over its audience in its evocation of the foundation of Rome from the ashes of Troy to the glory of the Augustan Age. Unlike his poetic successor, however, Virgil is alert to literary censorship under the reign of Augustus (63 BC-AD 14), Rome’s first emperor, and carefully navigates its perilous terrain.

Rome is great according to Virgil. It always has been. It always will be. But Ovid is not convinced, and he seeks to capture an epic world of uncertainty and destabilisation instead of “drinking the Kool-Aid” that flows from Augustus’ fountains.

Ovid’s graphic tales of metamorphosis begin with the story of Primal Chaos; a messy lump of discordant atoms, and shapeless prototypes of land, sea and air.

This unruly form floated about in nothingness until some unnamed being disentangled it. Voilà! The earth is fashioned in the form of a perfectly round ball. Oceans take shape and rise in waves spurred on by winds. Springs, pools and lakes appear and above the valleys and plains and mountains is the sky.

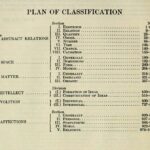

Lastly, humankind is made and so begins the mythical Ages of Man. And, as each Age progresses – from Gold, to Silver, to Bronze and finally to Iron – humankind becomes increasingly corrupt.

Ovid’s gods and humans never really escape the Age of Iron in the Metamorphoses. Throughout the epic, the setting that emerges in Book I functions as a brilliantly appropriate dystopic stage on which the poet-cum-puppeteer orchestrates his spectacles.

Drawing on the Greek mythology inherited by the Romans, Ovid directs his dramas one after another, relentlessly bombarding his readers with beautiful metrics and awe-inspiring imagery as that of Deucalion and Pyrrha, Arachne, Daphne and Apollo, Europa and the Bull, Leda and the Swan.

Metamorphoses by Ovid Book I read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book II by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book III by Ovid

Metamorphoses Book IV by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book V by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book VI

Metamorphoses Book VII by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book VIII by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses by Ovid Book IX read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book X by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book XI by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel

Metamorphoses Book 12 by Ovid read by A Poetry Channel