THE DISCOVERIES COLUMBUS DID MAKE WERE MORE IMPORTANT AND VALUABLE THAN THE ROUTE HE FAILED TO FIND.

It is certain, however, that Columbus was not the first European to cross the Atlantic. Documentary evidence supports claims that the Vikings reached the New World about AD 1000. And there is good circumstantial evidence, though no documentation, to suggest that both Portuguese and English fishing vessels made the crossing during the 14th century, probably landing in Newfoundland and Labrador. Columbus, though he sailed a different route, followed many Europeans who earlier had sailed westward across the Atlantic.

The best available evidence suggests that Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa in 1451. His father was a weaver; he had at least two brothers. Christopher had little education and, only as an adult, learned to read and write. He went to sea, as did many Genoese boys, and voyaged in the Mediterranean. In 1476 he was shipwrecked off Portugal, found his way ashore, and went to Lisbon; he apparently traveled to Ireland and England and later claimed to have gone as far as Iceland. By this time Columbus had become interested in westward voyages. He had learned of the legendary Atlantic voyages and sailors’ reports of land to the west of Madeira and the Azores. Acquiring books and maps, he accepted Marco Polo’s erroneous location for Japan–2,400 km (1,500 mi) east of China–and Ptolemy’ss underestimation of the circumference of the Earth and overestimation of the size of the Eurasian landmass. He came to believe that Japan was about 4,800 km (3,000 mi) to the west of Portugal–a distance that could be sailed in existing vessels. His idea was furthered by the suggestions of the Florentine cosmographer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli. In 1484, Columbus sought support for an exploratory voyage from King John II of Portugal, but he was refused. The Portuguese also underestimated the distance but believed it to be beyond the capabilities of existing ships.

In 1485 Columbus took his son Diego and went to Spain, where he spent almost seven years trying to get support from Isabella I of Castile. He was received at court, given a small annuity, and quickly gained both friends and enemies. An apparently final refusal in 1492 made Columbus prepare to go to France, but a final appeal to Isabella proved successful. An agreement between the crown and Columbus set the terms for the expedition.

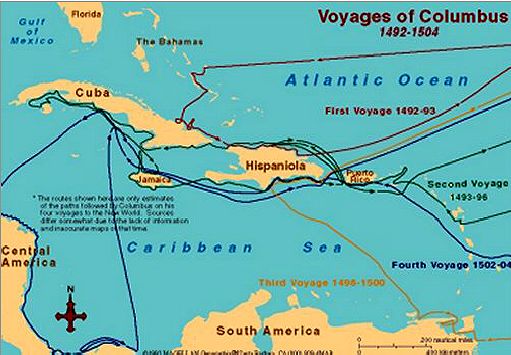

The Pinta, the Nina, and the Santa Maria were outfitted in the minor port of Palos. Columbus was aided in recruiting a crew by two brothers–Martin Alonzo Pinzon, and his younger brother Vicente Yanez Pinzon. They left Palos on Aug. 3, 1492. A landfall was made on the morning of Oct. 12, 1492, at an island in the Bahamas, which Columbus named San Salvador. The landing was met by Arawak, a friendly local population that Columbus called Indians. Some days later the expedition sailed on to Cuba, where delegations were landed to seek the court of the Mongol emperor of China and gold. In December they sailed east to Hispaniola, where, at Christmas, the Santa Maria was wrecked near Cap-Haitien.

Columbus got his men ashore, and 39 men were left on the island at the settlement of Navidad while Columbus returned to Spain on the Nina. Martin Alonzo Pinzon, who had explored on his own with the Pinta, rejoined Columbus, but the ships were separated at sea.

Columbus finally landed (March 1493) in Lisbon and was interviewed by John II. Then he went to Palos and across Spain to Barcelona, where he was welcomed by Isabella and her husband, Ferdinand II of Aragon. Columbus claimed to have reached islands just off the coast of Asia and brought with him artifacts, Indians, and some gold.